Part 3: What Kind of Propaganda is Country Music Making This Time?

Country culture, Zach Top, and Richard Petty in America's second eugenics movement (and also a defense of pop country)

If this is your first time checking in on this convo, here are some links to Part 1 and Part 2 for some background.

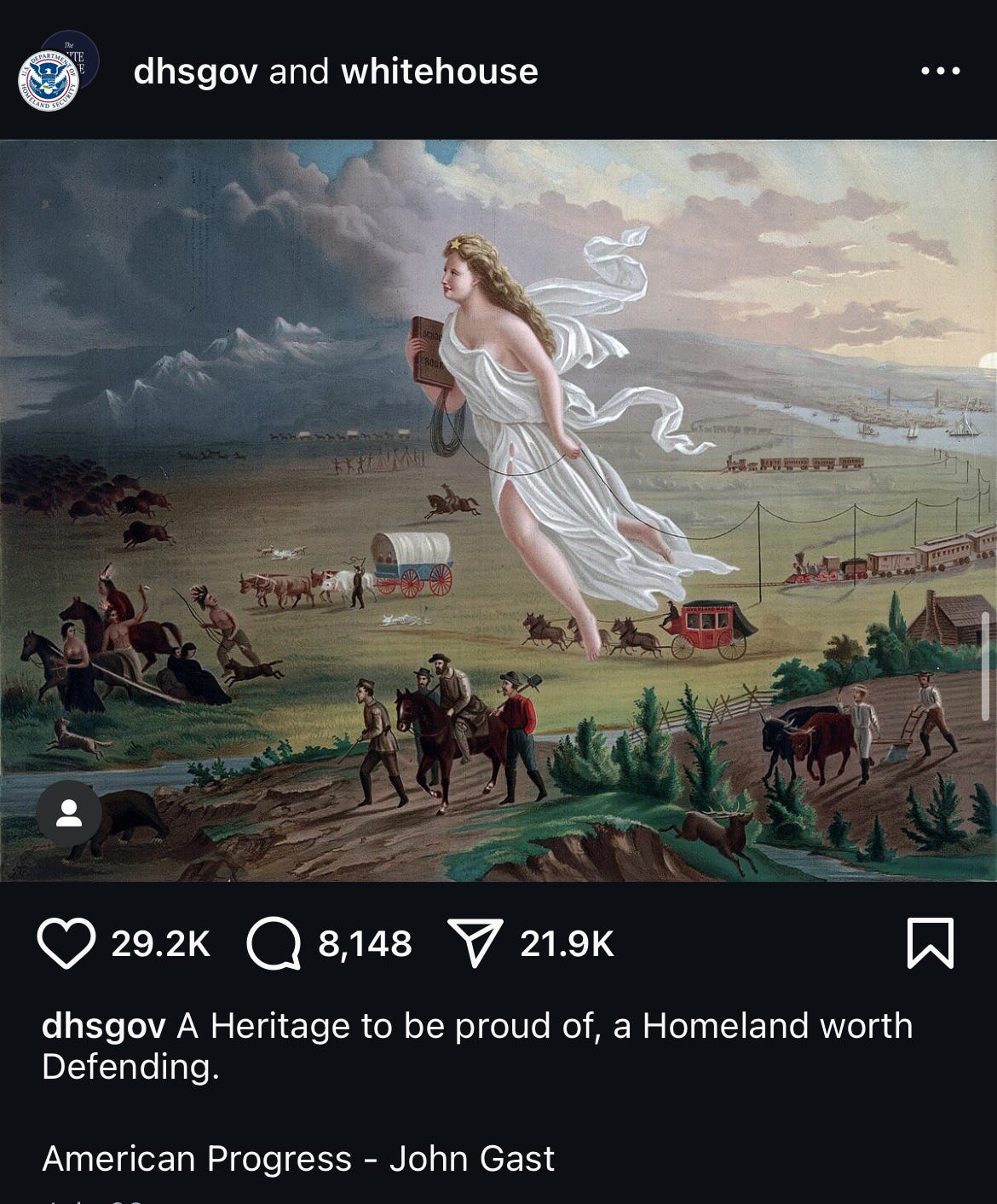

On July 23, the Department of Homeland Security posted John Gast’s 1872 painting, “American Progress,” with the tagline “A Heritage to be proud of, a Homeland worth Defending.” Gast’s painting depicts Progress as a pale, blonde-haired, blue-eyed angelic figure floating across the American frontier. In her wake, Progress is followed by a trail of White settlers. Her visage is the frontline of expansion, where light pushes back darkness, from which Indigenous people flee, and buffalo are hunted by settlers on horseback. The painting implies a racialized narrative of civilizational progress with the movement west symbolizing the burgeoning stages of White civilizational development. At Progress’ feet are the stagecoaches and wagons of pioneers followed by plowed fields and westbound trains until the most eastward point of the painting reveals advanced industrial infrastructure. And all of this civilizational progress is directly correlated to the advancement of White settlers as they displace Indigenous peoples and occupy their lands. A sign of their civilizing influence, the settlers are depicted in industrious form, working, travelling, or plowing, while a native family in the foreground is depicted in retreat and another group dances in the background.

The gender politic of Gast’s scene is striking. While the settlers are all men, Progress is the only White woman depicted in the scene. Despite carrying a spool of wire expanding eastern infrastructure, Progress is pristine. Her white gown and features are unblemished by the stains and soot of work, travel, or climate. Progress is literally above the fray. She floats above the landscape while her gaze stares into the westward horizon. Psychically and physically she is unattached to and unsullied by the people, place, and struggle beneath her, her only tether effortlessly unspooling behind her. She is a rootless apparition only connected to the mortal world through the expansion of White infrastructure. In Gast’s settler fantasy, settler colonial advancement is best depicted in pure White femininity unblemished by the frontier necessities undertaken by men.

Her depiction is nothing new. Representations of White women have often been deployed to symbolize the innocence of White domestic life. The softer, domestic complement to their male counterparts calloused by the public spheres of war and work, White women are positioned as innocent keepers of the hearth, unburdened by the moral strife of men on the frontlines. Their domain is the domestic, the private, the tender, the nurturing, and, as such, women are the objects of men’s protection. In long-standing tradition, there is very little that triggers American intervention like the perceived suffering of White women. White men and women are the progenative couplet of American moral panic.

The DHS’s contribution to the painting is also telling. While Gast’s painting depicts the active process of displacement and expansion, the government’s caption takes a defensive stance. The caption pairs conservation of home and heritage with an image showing White settlers actively (and violently) stealing home and inventing heritage. It would be foolish to go with an easy, gotcha interpretation that the conflation of heritage and expansionist aggression is a contradiction. In a settler colonial project like the US, displacement is heritage. To defend a settler’s world is not to refer back to anything inherently constructive but to defend the exploits of settlement.

This entire image—not simply Gast’s painting but its reemergence as an aesthetic tool of the American government—is a defining image of our era. The American project has had a few distinctive settler colonial achievements: the proliferation of the suburbs, the creation of the frontier, and the eugenics movement. These are all separate yet related creations made from the same ingredients and prepared in the same kitchen. While Gast’s painting pre-dates the eugenics movement, it nonetheless reveals the same cultural, political, economic, and environmental logic of settler colonialism that has undergirded every epoch of imperial expansion. In this sense, the eugenics movement is best understood as a reinvention of settler colonialism suited for times when the imperial demands on America’s capacity for war and work required redisciplining. Like the suburbs and the creation of the wild frontier, eugenics movements are built in the pursuit of creating the authentic White subjects pictured in Gast’s painting.

What was the Eugenics Movement? (hint: it’s more than pseudo-science)

Eugenicist logic starts with the naturalization of socio-political outcomes. Within a eugenicist framework, the consequences of the dominant political and economic order are transmogrified into the immutable characteristics of the individuals who bear them. The poor, for example, are not a creation of economic systems but are a blighted natural occurrence that must be pruned from our social ecology. Where bootstraps conservatives argue the poor have a moral obligation to adapt to being losers in the capitalist game, eugenicists argue the poor and other undesirables should be disqualified from the game altogether. In a eugenic framework, undesirability is a pre-moral, pre-social fact of existence. When it comes to America’s undesirables, their uselessness to the narrow confines of the imperial political order is a result of something as mute and amoral as their biology. It is simply a case of failure to thrive.

The ultimate end of the eugenics movement of the first decades of the 20th century was the radical disenfranchisement of those who could not keep pace with the growing needs of imperial expansion. Its targets were imperial capitalism’s inefficiencies: criminals, the unindustrious, those who were dependent on care and charity, sexual and gender nonconformists, and “dark-haired hill people.” Some of these targets could be couched in the medical terms of the time like “idiocy” or “feeble-mindedness.” But the political thrust of eugenicist logic could never be neatly concealed in strictly medical terms. With or without the sanitizing effect of scientific rhetoric, pathologization of nonconformity spread: women for being nonmaternal, the noncompliant poor for their indolence, and the disabled for their inability to easily assimilate into industrial society. Employing any means necessary, the eugenics movement revised the rolls of American citizenship, purging anyone incapable of conforming to an imperializing political order in need of soldiers to send abroad and industrial workers at home. Racist IQ tests maintained the established racial hierarchy in public sectors like the military, institutionalization kept the disabled from complicating America’s growing industrial workforce, diagnoses of hysteria kept women’s lives privatized, and sterilization kept the poor from existing. This period was defined by a massive explosion in the kinds of carceral institutions that could house prisoners, institutionalize women, and perform forced sterilizations.

One of the most common misconceptions about the eugenics movement is that it was primarily a scientific movement that lost its moral footing rather than a political movement happy to employ medical science as its most expedient technology. As rhetorical technology, scientific language appealed to the elites, presented an air of intellectualism, and provided just enough logical scaffolding to be respectable. For the powerful classes who took up the eugenicist cause, the line between scientific expertise and authority was just muddy enough to be politically advantageous.

Mischaracterizing the eugenics movement as a misguided scientific movement diverts energy away from striking at its political taproot. While the scientific errors and abuses that contributed to eugenicist ideology have been addressed, the social vision–its primary motivating force–never left the scene. The radical disenfranchisement embodied in rampant carceralism, segregationist distributions of capital, and the invisibilization of disability still fundamentally structure the limitations of contemporary American democratic practices.

To this point, the eugenics movement should not be understood as a sui generis right-wing movement in America. It did not apparate on the American scene. To the contrary, the eugenics movement has long, well-tended roots in American settler colonialism. The eugenics movement can be best understood as a settler colonial renewal movement in which the primary stakeholders of American power recommit the public to their fundamental tenets of capitalism, White supremacy, Indigenous ethnic cleansing, and the patriarchal family. At a crucial inflection point in American imperial growth, the vows of American life needed renewal. In this way, the eugenics movement not only defines the social order of its time; it also reveals the political, cultural, and economic lineage that made it the hegemonic ideology of the powerful. In eerie harmony with Gast’s settler colonial image of Progress, eugenicist ideology was aimed at continuing what leading eugenicist intellectual Henry Herbert Goddard called “the progress of civilization.”

Defining Eugenics Country

My conviction is that we are experiencing a new contraction in country music after a brief period of expansion. (Part 1 and Part 2 talk in more depth about the recent history that led us here.) What is emerging from the alt-country expansion of the last decade is a new movement in country culture aimed at establishing ideal American subjects. This movement hinges on the subtle yet profound slippage between revival and renewal. Where the former revitalizes the genre by nurturing the generative power of its diverse roots, the latter is a purification movement attempting to recover a mythic, univocal past. It is the difference between traditioned invention and revisionist nostalgia.

This is not news for some, but it still must be said: the US is not a natural occurrence. This country was built, not born. It is an ongoing project. It has a history that can be laid out even by someone (no matter how problematically) as facile as John Gast. Accordingly, shaping the ideal American subject is not coterminous with shaping our basic humanity. Eugenicist projects, however, collapse the difference between national belonging and humanity. In their framing, one’s capacity to meet the economic, political, and cultural demands of a nation is the essential measure of one’s humanity. There is no difference between patriot and person. This elision is a foundational building block of eugenicist propaganda, and it spawns a cornucopia of antisocial category errors: slavery is a natural occurrence; poverty and war are our natural state; women are inherently maternal; there are such things as Blue Lives. It will tell you dreaming about life beyond US imperialism is annihilationist and will perceive disloyalty to a flag as an existential threat to humanity.

As is usually the case, this new movement in country music is both a response to our moment as well as an assertion of its supremacy. One cannot help but notice the sympathies between an outspoken White segment of country music listeners returning to country music traditionalism and the broader political and cultural ascent of the MAGA movement. Undoubtedly, American culture is experiencing a eugenicist renewal. Boss Hog and Roscoe P Coletrain campaigned on explicitly eugenicist rhetoric, eugenicist Pinky and the Brain--Peter Theil and his half-baked braintrust Curtis Yarvin--have exerted outsized influence on conservative power brokers, and MAGA-merchandised concentration camps are the new pet project of red state governors. The lines of pathology are being redrawn around disabled, gender nonconforming, and other outlier groups who find themselves alienated from America’s right-wing national vision.

The eugenicist revival is also in other cultural spaces. The Manosphere is reviving disproven, polemical claims about racial and ethnic hierarchies. Recent TikTok discourse has revisited the age-old eugenicist question of whether disabled families should have children, Tucker Wetmore is pushing a viral bop about the superiority of blondes, and, with all due respect to dead horses, we all have seen the Sydney Sweeney genes ad. This renewed quest for the ever-narrowing authentic American subject occurs alongside the reemergence of immigration policies, practices of institutionalization, subversion of social safety nets, reassertion of racial and ethnic hierarchies, redirection of medical funds to the aims of the State, and naturalization of poverty that were distinctive of America’s first eugenics movement. Most telling, like the classic era of American eugenics, we are currently experiencing another carceral explosion.

The country culture industry’s role in building today’s eugenicist ideology is not in arguing for the supremacy of eugenicist ideology--we have politicians and podcasters for that. The culture industry’s emerging role is to develop a spiritual life for eugenicist ideology by vesting its practitioners with the stuff of our felt reality--imagination, desire, logic, feeling, grief, hope, fraternity, and narrative. Broadly speaking, culture helps incarnate ideology. It makes ideological commitments feel human and livable until those commitments become so enmeshed in our sense of reality that the world built by and for the powerful seems so obvious, inevitable, and natural that it feels like our own. Successful enculturation makes it impossible to disentangle life from the systems profiting off it.

Unlike the resoluteness of soldiers being fashioned by bro country, the ideal imperial citizen of our renewed eugenicist moment must be capable of drama. Driven by the need to authenticate the humanity of its idealized person, the eugenicist subject must display softness, sadness, intimacy, sincerity, likability, and play. They must be able to sell the creation and enjoyment of fully-realized, optimized domestic lives. A successful incarnation of eugenicist ideology must be capable of showing the signs of a fully-lived life: crying, laughing, bargaining, flirting, and reflecting. Such a subject must be capable of holding complexity and even sincerity.

A convincing eugenicist subject must mimic our humanity. Their spiritual life must be dynamic enough to make meaning in a wide-enough array of situations that it does not collapse the moment it encounters contradiction or suffering. Even if it ultimately produces fragility in its subjects, a successful enculturation of right-wing ideology must also produce persistence through zealotry, fantasy, or ignorance. Like the innocent White angel haunting the frontier, it must compel belief, hope, empathy, and action. Ultimately, the eugenicist subject can possess full self-awareness in every realm except in identifying the loyalties and powers that ground their orientation to the world.

Crucially, what is distinctive of a eugenicist culture is not the presence of practices that transparently boast the superiority of blonde hair and blue eyes (though this is also an emerging trend in parts of the entertainment industry). Instead, it is marked by the ways it bestows upon its most desired citizens the appearance of nativist authenticity. Our current era of country has retained much of the autobiography and noncommercial artistry recovered by the alt-country era. The songs feel personal, intimate, and sincere. This feeling of rootedness in occupied soil, this attunement to the drama of the American project, is the bulk of the propagandistic work. Accordingly, our era of propaganda largely fosters connection to the art through the particularity of the artist. Its power is not in saturating the airwaves with widely-accessible commercial slop but in narrowing the definition of authentic country identity to a vanguard of well-branded cowboys.

A Contracting Country Culture Canon

In recent weeks, the country music side of TikTok has taken to ranking the top ten artists of all time. To be clear, this trend does not rank a listener's favorite artists; it ranks the ten artists a listener thinks are most foundational to the genre. It is the difference between saying Lance Stevenson is my favorite player to watch and saying Michael Jordan is the greatest player of all time.

These lists tend to include the same staples: Willie Nelson, Alan Jackson, Merle Haggard, George Strait, Waylon Jennings, Hank Williams, Jr., Toby Keith, Keith Whitley, George Jones. The pattern is pretty clear: the majority of these top tens are exclusively White men. The omissions are telling. There are no women and no people of color. These lists don’t even include male icons like Roger Miller who wore too many turtle necks and did too much ketamine to be perceived as cowboys. An equally revealing yet more subtle omission is the absence of country music’s most recent batch of mega-successful White men. Acts that liberally incorporate their pop influences, including well established acts like Jason Aldean, Luke Bryan, and Morgan Wallen, are all absent despite their outsized influence on the genre in recent decades. This lack of diversity is so restrictive that it excludes (I can’t believe I’m typing this phrase) the diversity of White men. Only the ones who look like Richard Petty get included.

The remarkably narrow monocrop represented in these rankings alludes to the boundaries of what these fans consider to be authentically country. Their rankings of the greatest country musicians are not rankings of the most commercially successful artists, the artists who most advanced the genre, the artists who defined their eras, or the artists who best represent various subgenres within the country music landscape. These rankings are the result of fans insisting that a subset of country music artists supplant the diversity of country music in order to establish a small, monopolistic representation of the whole of country music. It is a matter of sorting out who best embodies a single, ideal country aesthetic that converges on a few common features: conventional, old-school masculinity; auteurist sensibilities; a lack of easily recognizable pop influence; traditionalist sounds like pedal steel, fiddle, train shuffles, etc.; songs written in the vernacular of the American homeland.

In every way, this canon of men represents the mean of American culture. They are political but not too political. They are rule breakers but only in marketable ways. They have the winsome softness that bro-country lacked but are not soft enough to transgress the boundaries of gender and sexuality. Their lore is riddled with stories about fraternity and charity but not solidarity. Unlike artists like Vince Gill or Emmylou Harris who have been unparalleled collaborators in addition to being remarkable individual talents, the greatness of these lauded figures is in their individuality. These artists are not canonized because they challenge the limits of country sound and culture. Instead, they are canonized for the ways they set up camp in the cool center of country culture. They do not push the boundaries; they define the core.

It’s pretty obvious that these rankings are not built to represent a comprehensive history of country music. These rankings are an erection of idols for our present moment. They are a reenactment of American greatness drawn from the Yellowstone nostalgia that has its teeth in contemporary country culture. This is a ranking of a fan’s admiration more than their assessment of the genre. And much of what this canon lauds is the familiarity of these men.

This hagiography of Richard Petty impersonators represents a shift back to what feels like home in America. Where bro country was about motivating men to take their American rage overseas, and boyfriend country was about testing the commercial limits of country music, our current era is about trying to sell the image of morally-uncomplicated down-home belonging. It is about giving the sense that White country culture is an authentic artifact native to the Americas. This pseudo-indigeneity is demonstrated by turning up the twang, suppressing pop elements, and writing about their everyday joys and griefs of life in America. It gives the effect of belonging to something older than the present but not without giving up the privileges of Whiteness and imperial hegemony.

Zach Top (b.h.h.)

There is no artist who better defines this return to the domestic core of idealized country culture than rising-star Zach Top. Talking bad about Zach Top on the internet can get you in some hot water pretty quick. Turns out his fans are the cowpoke equivalent of Swifties. Their unbounded adoration for him spawns a panoply of incoherent yet vigorous rationalizations for his every move. In fact, a number of top ten rankings include this babyfaced industry darling despite having released only one album in his very young career. His presence on these lists is the precious gift of an unconscious tell revealing that these rankings are not built on historical significance but preference for fantastical men. For many, Zach Top is the most Petty of the Richard Petty resurgents.

Zach Top’s rising prominence in the country scene brings up the difference between nostalgia and camp in country music. Country music is no stranger to camp–Dolly’s tackiness, Charlie Crockett’s $10 cowboys, polyester honky-tonk. Camp is everywhere in the tradition. It’s been a way of negotiating the commerciality of country music. Camp makes it plain that there is an element of commodified fast fashion in every piece of country music. It disarms this commodification by exaggerating it, letting the audience in on the secret that what they’re getting is country content in a single-use plastic form. It is a reminder that bonafide authenticity is not possible in a commercial genre. The overperformance of camp draws attention to the compromises that have to be made to render a market-viable representation of country culture.

What Zach Top is offering up is not camp but nostalgia. He is taking an imagined reconstruction of the past sanitized of its complexity and dressing it up in the aesthetic trappings of the past. It is historical cosplay invested in zombifying the past, putting its dead parts to the uses of the present without resurrecting the relationships and concerns that animated it. This is not only dangerous because it relates to the products of the past as they are decontextualized from the motivating questions that produced them, it also scratches the traditionalist itch left by bro and boyfriend country without curing the social eczema that produced it. Nostalgia is a convincing poltergeist for history, and in a nation where our real history has been radically suppressed, there is little real history available to distinguish between the ghost and the real thing.

Sonically, Zach Top serves up fine enough music. Fans have good reason to enjoy his work. The palatability of his songs is beside the point. Top’s project is doing little more than offering up a karaoke version of previous country artists, manufacturing a marketable meme of a sound people miss. Offering little more than reissued versions of 90’s country hits, Top’s music does not invent within the tradition but reenacts it. It is not fresh as much as it is Frankensteined.

The thing is, though, that the pined-for sound Top is harkening back to never went away. It still exists. Fans can still listen to Alan Jackson, Clint Black, George Strait, and John Anderson. Their catalogs did not disappear with their commercial dominance. The original songs have exhausted most of their commodity use; now they simply exist to be enjoyed. The tangle of contradictions driving Zach Top’s success is that no one is making new money off of old art, so he sets about selling commodified, historical authenticity. Top’s success is not a revival of old sounds but a renewal of their commodification.

An Aside on Pop Country

One of the reasons I refuse to be deferential when gatekeeping country bros argue that pop music ruined country music is not because I want to defend the enshittification of country music typified in bro and boyfriend country. To the contrary, understanding that country music has always been a pop genre is crucial to understanding country music’s cultural location. As a commercial genre, unlike its old-time and folk counterparts, country music has always been concerned with making its sound appealing to contemporary audiences. This is why country music has always followed the latest pop trends, conservatively adapting the pop inventions of its non-country counterparts. (Perhaps the slow, conservative nature of country’s pop implementation lends to the confusion that if country music is not leading pop innovation, it must not be a pop genre at all.) Lush string arrangements, R&B conventions, gated drums, wah pedals, and distorted guitars all made their way into country music as these elements of pop music became mainstream.

Country music has never chosen the inaccessibility of avante-gardeism or rigid traditionalism. Accessible and with the times, country music is akin to single-use goods created in bulk, distributed widely, consumed for a short time, and quickly replaced by the next similar commodity. This is not to say that country music is not enjoyable, does not offer meaningful insight, or is not a site of creativity. All these goods can exist in a medium that is also churn-and-burn. Most American staples also fit this mold: hot dogs, High Life, cigarettes, blue jeans, car culture. Country music may champion, and even preserve, twang in American culture but it does so via commercial accessibility. While there is room to critique imbalances in the ratio of pop-to-twang that has always been the constitutional alchemy of country music, absolutist critiques of the presence of pop itself provide slippery cover for folks who feel their country music is too feminine, too Black, or too queer. Where initial, nondescript frustrations with pop influences in country music can open interesting lines of criticism, wholesale critiques of pop itself is a non sequitur often produced by anti-social reactionism or nostalgia.

In the rise of eugenicist country, the emerging meaning of anti-pop sentiment seems to be voicing a nativist impulse. Echoing our current political climate, resentments toward pop influences in country music express a closed border sense of country identity. Across country music spaces, bros are inventing the revisionist orthodoxy that pop ruined country music. As is the case with most orthodoxies invented by bros, their body of evidence is little more than the hollow fabrications of myth and nostalgia thinly veiling their own desires for policing country culture.

By trying to erase the long-standing presence of pop influences in country music, this nativist critique ultimately works to naturalize the commercial mechanisms that produced the very country lauded by said bros. In the 90’s, Alan Jackson was borrowing pop production; in the 70’s, Waylon was borrowing pop musical conventions; in the 60’s, George Jones was borrowing pop tone; and so on down the line. Filtered through the forgetful historiography of nativist country, with enough time and history what was considered pop innovation at its time corrodes into pure, single-barrel country music. The open question of how to balance pop influences and twang inheritances that has structured the entire tradition of country music becomes obscured in favor of falsely recasting the cultural hybridity of country music into a single, aboriginal source.

This lie of single-origin nativist fiction obstructs our ability to regulate the commercial mechanisms that produce country music. Country music, the product of hillbilly culture negotiating record conglomerates, good ole boys clubs, advertising strategies, nepotism, market calculations, and upper-middle class gatekeepers, becomes simply “the people’s music.” Echoing the eugenicist flattening of built and natural worlds, the commercial considerations that have always been a part of country music become so invisible and normal that they appear as natural as country music’s distinctive twang. The difference between brand image and genuine artifact, Marlboro marketing and cowboys, Carhartt looks and Carhartt shit disappears. There is only the convincing though uncanny simulacrum of authenticity in a genre that rewards authenticity with power and influence. Collapsing the difference between RealTree and real trees provides the ultimate camouflage.

Building Angels

In Gast’s painting, none of the characters in the scene share a gaze. The White settlers move forward, directing their gaze westward or at their work while members of retreating Indigenous families look fearfully back at Progress or at the ground in dejection. The only ones paying attention in any way are the displaced. The rest are attending to their labors, to traversing the frontier, to building the New World. The settlers are depicted without fear or moral dilemma. At no point do Progress or the white settlers have to meet the gaze of the families fleeing the expanding borders of Gast’s frontier–they are unified in their obliviousness. They simply progress across the landscape sanitized in Progress’s softness and the nobility of industriousness.

The work of eugenics country is the work of constructing the angelic poltergeist of Progress. It is the work of manufacturing the sincerity and innocence of settler colonialism. It is the task of modeling the oblivious gaze–looking off into the distance and avoiding the moral inbreaking of face of those impacted by the brutality of imperial conquest. Eugenics country lends the theological force of poetics to the unromantic confrontations of imperial expansion, reversing the trajectory of our responsibilities. Without the fiction of Progress’ angel, the settlers are not passively following her visage across the frontier but are actively advancing against its Indigenous inhabitants. The work of eugenics country is to unspool the lines of the American establishment into new frontiers, constructing a sense of continuity and history that is little more than mythic nostalgia.

Eugenics country is not about returning to tradition but returning to the old forms of power associated with those traditions. More than reviving a sense of domestic American identity, it is about reconstructing a domestic American role, the role of the settler that became the worker that became the soldier that now becomes the patriot. More specifically, our current era of country music propaganda is about making the role of such an obedient citizen–the cop, the able-bodied employee, the grateful tenant, the trad wife–feel liveable. Hank Williams, Jr. blew wind under the wings of White flight, bro country hardened men for war, and eugenicist country is greasing the chokehold of a tightening domestic order. It reconstitutes markets around the sentimental ruins of White American domestic life–90’s sweetness, down home twang, gentle masculinity–and calls it tradition.

This essay is incredible. Thanks for sharing. Is there a part 4?